On March 5, 2025, Frederick “Fred” Weichel, a man who served 36 years in prison for a murder he did not commit, visited Yale to speak on his wrongful conviction and the lengths it took to reach his ultimate exoneration. Key to overturning his conviction was the role of photography conservation in uncovering the evidence tampering of a crucial police binder. Extensive expertise from Lens Media Lab Director and expert witness Paul Messier drew upon photography conservation techniques to identify the exculpatory material within the binder. Messier and one of Weichel’s attorneys, Mark Loevy-Reyes, joined Weichel during his visit to Yale. Together, they met with advanced clinic students at Yale Law School (YLS), followed by a panel discussion focused on the intersection of art, law, and justice, open to the wider Yale and New Haven communities.

An innocent man served 36 years in prison. Photography conservation paved the way to his exoneration.

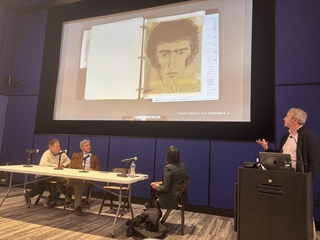

Paul Messier discusses the police binder that led to Weichel’s exoneration.

Throughout his life, Weichel has faced the unimaginable: lost time and lost life. Decades-long injuries and damages comprise the cost of maintaining innocence amid unchecked and unjust policing, incarceration, and criminal legal systems designed to convict. Yet, through it all, he remains staunchly unwavering in his belief in humanity and is committed to more just outcomes in future cases of exoneration and wrongful conviction. Weichel’s case underscores the salience of taking creative and strategic approaches to advocacy and litigation, bringing together cross-disciplinary expertise in new and unexpected ways in the fight to break down systemic barriers to justice and build reforms in their place.

Student Engagement: Fostering the next generation of advocates.

During his visit to YLS, Weichel engaged with a class seminar at Baker Hall, speaking with students involved in clinics that focus on matters adjacent to direct representation and criminal justice. The clinics included the Criminal Justice Clinic, Challenging Mass Incarceration Clinic, Mental Health Justice Clinic, and Criminal Justice Advocacy Clinic. Students addressed Weichel with questions regarding his experiences bringing actions to challenge his conviction, handling the physical and emotional toll of incarceration while serving a life sentence without parole for a crime he did not commit, and navigating issues surrounding the police culture that led to the withholding of the evidence so crucial to his exoneration.

In response, Weichel discussed ceaseless efforts to maintain and prove his innocence, refusing to plead guilty to lesser charges. Instead, he worked with counsel to continuously tender public records requests for exculpatory material over nearly four decades, until one, at last, produced the pivotal police binder that reopened the investigation and instigated new suits. He shared harrowing details of the harsh living conditions he faced during incarceration, navigating cultures of fear and violence compounded by a reluctant dependency on and mistreatment by prison officials. He described the nature of police misconduct and corruption rampant not only in his case but also as a pattern at large, pointing toward work to reform policing policies, operations, and accountability.

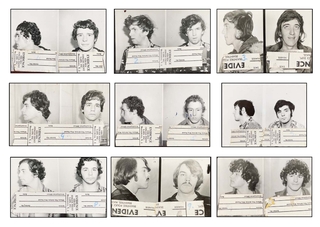

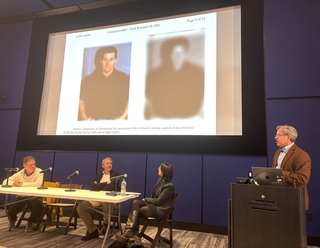

The original photo array with Fred Weichel at the bottom right.

Students also asked Loevy-Reyes and Messier to elaborate on elements of exoneration and wrongful conviction litigation. Loevy-Reyes engaged students in discussions of the remaining legal challenges entailed by ongoing federal and state civil suits brought on Weichel’s behalf. He first described the defense’s rebuttals to flawed prosecution theories in the criminal trial, leading to Weichel’s exoneration, which laid the groundwork for the civil process to begin seeking damages and compensation. He then explained the principal legal claims being made in the civil suits based upon the suppression and fabrication of evidence. Furthermore, he shared insights into obtaining and working with expert witnesses like Messier and preparing them to testify at deposition and trial. Messier spoke to his experiences as an expert witness, detailing the forensic process involved in identifying the exculpatory evidence; the forensic analysis required an intimate understanding of the material characteristics of photographic paper. He addressed the role of photography conservation in proving Weichel’s innocence and obtaining his ultimate freedom.

Public Education: Giving a voice to exoneration and wrongful conviction

Following the seminar, Weichel, Loevy-Reyes, and Messier spoke to a public audience in the Humanities Quadrangle as part of a panel discussion moderated by Fiona Doherty, YLS Deputy Dean for Experiential Education and Nathan Baker Clinical Professor of Law. The panel discussion expounded upon the nature of Weichel’s case, exploring details of the crime, the 1980 shooting and murder of Robert LaMonica in the Town of Braintree, MA, and its surrounding circumstances, characterized by the lack of any eyewitnesses or physical evidence. The investigation instead relied entirely on a composite sketch based on identification testimony by a teenager who had seen a man running from the incident under a streetlight, from at least 180 feet away, and for approximately one second. This testimony had also been influenced by a deal that the teen had made under coercion by police officers to implicate Weichel.

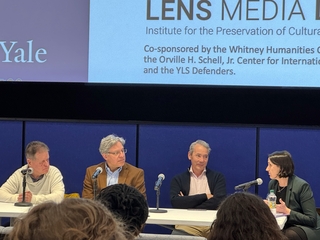

Fred Weichel, Mark Lovey-Reyes, Paul Messier, and Fiona Doherty during the panel discussion.

Over thirty years after Weichel’s conviction, the discovery and disclosure of a key piece of evidence—a police binder containing a report incriminating an alternate suspect, Rocco Balliro—significantly altered the direction of the case, exonerating Weichel. Referred to as the Leahy Report after the detective who authored it, this document had been withheld from disclosure to both the prosecution and Weichel’s counsel during the original criminal trial. Instead, it had been hidden and buried by investigators and police supervisors within basement files of the Braintree Police Department, known as the “Basement Archive.” One of many instances of gross police misconduct and conspiracy, the suppression of this evidence was a deliberate effort to cover up for Balliro and frame Weichel in his place. Only upon a public records request made by Weichel, amid his ongoing efforts to maintain his innocence, did this report finally come to light. It was the Leahy Report that brought Messier onto the case.

Forensic analysis: using imaging techniques from photography conservation

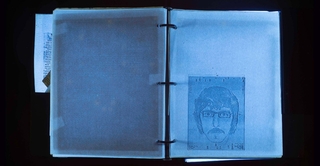

As a part of the reinvestigation into Weichel’s case, Messier explained how he applied ultraviolet (UV) imaging, specifically near UV-induced visible fluorescence, to each page of the binder, including the Leahy Report. This imaging technique allowed him to identify physical signs of police tampering within the binder. In particular, he discovered a reordering of pages, done to divert the blame from Balliro to Weichel. Based on the material characteristics of the paper used for the binder pages, the correct ordering of the pages could be deduced from visible indicators of chemical degradation of pages pressed against one another. Under UV, signs like matching tape marks or mold residue on the fronts and backs of the papers presented clues as to how to return the binder to its original state, uncovering and undoing the steps taken by the police to frame Weichel deliberately. Messier included demonstrations of these physical, material characteristics of the paper to the audience, displaying visuals of the binder pages viewed under UV. Ultimately, the binder’s recovered state clarified that the eyewitness identification referred to Balliro. These findings were bolstered by the textual content of the Leahy Report itself, stating that at least 10 people had told Detective Leahy that Balliro more closely matched the description of the culprit.

The binder displaying tapered evidence under UV light.

Legal claims: suppressing exculpatory evidence and fabricating false eyewitness identification

Loevy-Reyes discussed the legal proceedings of the case, addressing the ways that Messier’s forensic analysis and its subsequent unearthing of new exculpatory material have been used to undermine prosecution theories that had been based on tampered evidence. In addition to the criminal trial resulting in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts dropping all charges against Weichel and establishing his innocence, Weichel filed civil lawsuits to sue the police officers for fabricating evidence, bringing suit against the Town of Braintree, Braintree police, the City of Boston, Boston police, and Massachusetts State police. These suits involve federal claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and state claims under Massachusetts law, bringing counts for violations of due process, federal malicious prosecution, conspiracy to deprive constitutional rights, failure to intervene, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and indemnification.

The Lehey report in the missing police binder.

The legal claims made by Weichel’s attorneys have been based on the suppression of exculpatory evidence—the Leahy Report—and the fabrication of false eyewitness identification, as efforts to mislead and misdirect his prosecution. Separately, Weichel also brought a state compensation case against the Commonwealth of Massachusetts under Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 258D to seek compensation for injuries and damages sustained as a result of his erroneous conviction.

During his presentation, Loevy-Reyes also showed the audience one of the photo arrays used during the initial trial resulting in Weichel’s wrongful conviction. He demonstrated the leading questions and suggestive photo identification procedures conducted by the police officers to misconstrue Weichel as the perpetrator of the crime. To underscore the unreliability of the identification process used, Loevy-Reyes provided additional commentary on a study by psychologist Elizabeth Loftus on the inaccuracy of eyewitness reports, emphasizing the face perception and information loss that occurs when recalling events seen from a distance at night. He and Weichel also contextualized the crime for the audience by shedding light on the 1980s Boston organized crime world run by James “Whitey” Bulger that produced a culture of police misconduct and corruption.

Mark Loevy-Reyes discusses the Loftus report, evidence used to depict the science behind eyewitness reports.

Wrongful conviction: living through nearly four decades of incarceration

Throughout the event, Weichel described the ways his unlawful arrest, prosecution, and wrongful conviction have shaped him personally. He elaborated on his experiences physically and emotionally navigating the carceral system while steadfastly maintaining his innocence. At the time of his arrest, Weichel was 28 years old, a Head Start teacher and a graduate of the University of Massachusetts. He had had a close relationship with his mother and had been in a serious romantic relationship with a woman he intended to marry.

Weichel discussed the mental and emotional distress of being deprived of the chance to be present in the lives of his loved ones, many of whom passed away during the time of his incarceration. He relayed accounts of his imprisonment, including descriptions of his conditions detained in maximum security prisons, including the notorious Walpole State Prison: the injuries and damages he suffered—being stabbed twice, and having his jaw broken and subsequently wired shut for weeks—as well as inadequate medical care; his experiences surviving several stints in solitary confinement, or “the hole”; and his interactions with and development of community among other incarcerated individuals. While in prison, he saw others become dependent on the system, a reflection of the ugly realities of recidivism: many lucky enough to get out were often quick to return. Others’ spirits broke, and their mental health deteriorated under the strain of the prison system.

Mark Lovey-Reyes, Paul Messier, and Fred Weichel smile after the panel discussion.

In response to an audience member’s question on how he managed to keep his spirits high across nearly four decades facing such conditions, Weichel stressed, with characteristic positivity, the importance of continuously seeking out and staying rooted in the silver linings. Finding ways to stay preoccupied—whether by working within his capacity to address others’ needs during their shared incarceration, or by maintaining a steadfast hope in the possibility of eventually being vindicated—kept him grounded in his raison d’être beyond imprisonment. While he has maintained this attitude after his release, he nonetheless acknowledged the challenges of adjusting to life following such a lengthy confinement. He expressed the general lack of resources provided for navigating reentry and the transition back into the community, having embarked upon the process predominantly on his own.

Recounting stories of adapting to his life upon release, he shared his bemusement upon seeing people talking to themselves on the street, only to learn later that they had just been on the phone through technologies he hadn’t encountered previously, and his shock upon buying coffee for the first time and discovering how much the price had increased. Addressing the psychological aspects of reentry, he discussed how his imprisonment had also resulted in the loss of natural psychological development: He still psychologically felt like he had remained in his late 20s despite reentering society in his 60s. In his new life as a free man, he needed to confront this incongruity.

Freedom: the final reckoning

Freedom is new territory. For an innocent man, freedom has been a strikingly hard-fought battle. In the years since his exoneration, Weichel has confronted the time he has lost and the time he has left, the lives he could have led, and the life he ultimately has made for himself. As a result of an unthinkable fault in the system, Weichel has paid the cost of innocence, emerging at last a free man—the free man he always should have been. Having attained justice, he now makes up for what he has lost. He focuses on healing, reestablishing relationships with his community, and traveling to places he had only been able to imagine for so long. What remains is a final reckoning with the nature of freedom and what it fundamentally means to be free.

Events sponsored by the Lens Media Lab at Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, in partnership with the Yale Law School Defenders, the Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights, and the Whitney Humanities Center.